The last time I saw The Cure in concert was in 1989. I was freshly graduated from university and had just started my first (and only) full-time job. That job was in book publishing at Beacon Press in Boston. By taking that job I had formally “left” the music business, the industry I had been sure I was going to work in for several years at that point. (I had started working at WPLJ radio in NYC while still in high school, and many alums of WBRU FM, the station where I then worked in college, had gone on to high-powered jobs at MTV, Rykodisc, and so on.)

It was also the final year of my relationship with my first really serious love/soulmate/partner and we were on the rocks. He was in his final year at Brown. We were living together in Providence and I was commuting daily to Boston for work. I was exhausted from the constant work on the relationship and the constant demands of the day job. I was in a time of transition and still unsure how a lot of things were going to pan out, or if they were going to pan out. I was desperate to start my career as a fiction writer but even with a two-hour train commute and an early model Toshiba laptop I was creatively drained and unable to accomplish much of anything.

As it turns out The Cure were in a similar state when we saw them that September at Great Woods (the outdoor venue between Boston and Providence, later renamed the Tweeter Center, and now called the Xfinity Center). The Great Woods date was the final one on their North American tour (and supposedly was to be their last tour ever though I think I had not managed to read that news before the concert).

The 1989 set list looks epic. I remember being pleased they played some of the more obscure tracks I loved from their earlier albums. The concert was also plenty long–three encores, including a final one that included the members of opening band Shelleyan Orphan and which sounded, frankly, kind of like a mess. But ultimately my partner and I turned to each other at the end of the night like “that’s it?” The band had seemed to me to be going through the motions and not much else. I didn’t feel the connection I was expecting.

It was perplexing. But was it the band or was it me not connecting? Had I outgrown The Cure, or was it that I was so wrapped up in the life struggles of being early twenty-something that I couldn’t enjoy the moment? At that point in time I was about the hugest fan of The Cure I could be: they were the rock band I was most into of all time, surpassing The Police (who had surpassed The Beatles).

Flash back to April of that same year, to my 23rd birthday party, at which I had performed “The Walk” (and a few other songs) with musician/tech nerd Jon Drukman, whom I had never met before that day, but we knew each other from an alternative music discussion group on the Internet. (I had been the manager of the Brown University electronic music lab and had lots of sequencing software for my Mac and Jon brought down a Yamaha DX-7 that afternoon and we worked up a set. And yes, the Internet did exist back in 1989 even if only a few of us truly nerdy were on it at that point.) I had spent hours and hours deconstructing The Cure’s songs in the mid-1980s, continually marveling at how Robert Smith managed to completely bypass all the bombast and technical hype and musicality dick-sizing of British prog rock as well as all the anti-musicality/anti-poseur bullshit of the British punk scene to go straight to creating incredible well-made songs with sometimes deceptively simple ingredients. What did I do with all my college courses in music theory? I took apart Cure songs.

When Disintegration came out, it melted my brain. One of the early short stories I wrote in an intermediate fiction writing class at Brown bore the title “Fascination Street” because there seemed to be some aesthetic connection between story and song that I couldn’t otherwise articulate. I went to see the Cure concert film In Orange in the theater. (And then bought the video.) On my commute my Walkman was rarely without Pornography, Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me, or Disintegration, dubbed onto cassettes from the CDs.

I was, in short, a fan.

I left that concert at Great Woods feeling like I was extremely glad I had been there, but as concerts go that it had not been that great. What was wrong with me? Was it me, or was it them?

At the time I figured it was me, but apparently I wasn’t the only one who felt that they’d been lackluster. As review of the concert I discovered recently, from MIT’s newspaper The Tech put it, “After having played the same set for five months, the band performed like machines. They sounded right, but they did not feel right. They seemed tired, as if they just wanted to get it over with.” That matched my experience of the concert: the band seemed like they were straining and not quite reaching what they wanted, they just didn’t have the oomph. They didn’t connect.

Years later I would read interviews with Robert Smith stating that was one of the worst shows he could remember. They were so exhausted by both the grueling work of being on the road and the strife within the band, this was why he had been saying it would be the last tour and possibly the end of The Cure. In one interview I cannot now find again he says he was against The Cure turning into an “arena” band and he was ground down by playing these huge venues–and having the identity crisis that went along with it.

You and me both, Robert. We were both mentally tapped out and eager to move on to the next artistic phase of our creative lives but so weighed down by everything that neither of us could quite figure out what was supposed to come next.

For me, ultimately, it was a breakup with that boyfriend, a move to Boston, and then quitting the day job entirely to pursue writing full time (by getting into Emerson’s writing MFA program). For Smith it was severing ties with Lol Tolhurst, the other founding member of the band and his childhood friend, who had been booted from the band during the recording of Disintegration.

As it turned out, that September 1989 concert was not the end of The Cure at all, it was the beginning of several years of commercial (and critical) success, once Smith accepted that The Cure were in such demand that there would be many more tours of huge arenas. (If you’d like to see details of every Cure show ever, check out https://www.cure-concerts.de, see the set list from that Great Woods show at https://www.cure-concerts.de/concerts/1989-09-23.php)

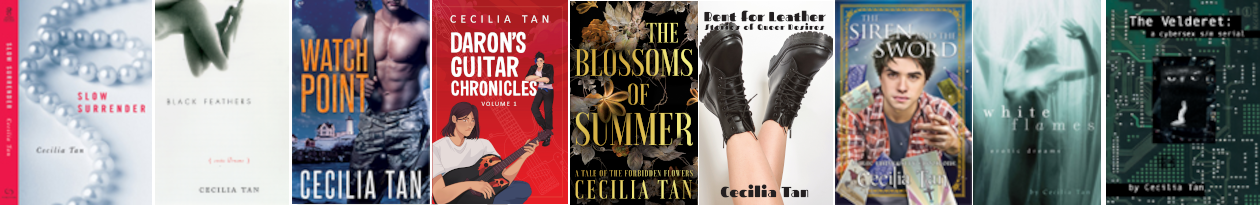

Flash forward 27 years. I’m at the highest level of commercial success I’ve yet reached as a fiction writer. (One of my recent novels was sold in Target, won some major romance awards, and I bought a car with the royalties.) The world’s finally caught up to what I’ve been doing. The Cure, meanwhile, haven’t released an album or toured since 2008 but when they announced in November that they’d be touring North America for the first time in eight years (other than some headlining gigs at Coachella and the like) the shows began to sell out quickly. The places they’re playing are not small and they seem to have sold them out handily.

So it was that I put on a leather jacket that is 25 years old, and a T-shirt of the same vintage, and some black lipstick (much newer) to head down to the Agganis Arena for the show. It was a beautiful summer day, sunny, not overly muggy, and as I sat in a sardine-packed Green Line car out of Park Street I tried to pick out who else might be headed to the show. Not the folks in Red Sox gear (who mostly exited en masse at Kenmore) but perhaps the woman sitting next to me in the ’50s throwback rockabilly dress? The colorful yet butch girl with piercings in her lip holding the railing above me? Yes to both, as it turns out. The crowd was decidedly less old-school Goth than, say, the acoustic Peter Murphy show I went to last month, with a much wider range of people, many more from the suburbs.

It was 7:25pm when I got off the train outside the arena. I was holding a ticket for Floor 1, the general admission area at the front of the stage, and we had a separate entrance and wristband. We also had a separate restroom–an auxiliary hockey locker room that had more showers (ten) than toilets (two, plus one urinal)–and I was in that restroom at 7:30 on the dot, making my last pre-show bladder-emptying before preparing to get as close to the stage as possible (and then not move). Also at 7:30 on the dot, The Twilight Sad took the stage to open the concert.

I don’t think I’ve ever been to a concert where the music began at the time printed on the ticket. I would say not even 10% of the audience was present yet. I hurried out to the floor and was pleased to discover I could easily get within five yards of center stage. That’s how few people were there. I ended up only three-deep from the rail and right in front of where Robert Smith’s mic would be set up, though I didn’t know it at the time since The Twilight Sad’s lead vocalist James Graham was positioned several feet to stage right.

The Twilight Sad are very sonically influenced by The Cure which made for a very pleasant experience for Cure fans who weren’t familiar with them. I’d describe it as shoegaze meets The Cure, basically. They’re from Glasgow and I iTunes-purchased the song I liked best from their set as soon as I got home to wifi. (“There’s A Girl In the Corner” See them perform it on KEXP below.)

The openers left the stage by 8pm and then came the wait. I got chatting with the people around me close to the stage. Some were seeing The Cure for the first time. Others had seen them more than 20 times and were worried this might be the last Cure tour ever. (I refrained from saying that Robert now has a 27+ year history of saying that things are the last whatever, last album, last tour, and that so far it hasn’t been the last one of anything yet.) We all agreed that in heterosexual couples it has to be the woman who goes to get the beer, because we can move through the crowd more easily without resistance, not because we’re smaller but because we’ve mastered the “scuse me, scuse me” and people will get out of your way when they see you carrying two beers, they assume one’s for the guy who’s holding your spot at the front. (Three of us women who were there alone stayed put and did not get beer in the first place.)

I forgot to look at the time but I think it was 8:36 when The Cure took the stage. I suppose I could check the timestamps on my photos if I really cared, but the opening video graphic seemed to be saying to me that we were entering a time machine going backwards and so time really wasn’t going to matter:

A note about the visuals: they very cleverly have five tall video screens, very similar to Adam Lambert’s setup (though he has four) except instead of every song featuring various video footage, much of the time the screens show portions of the stage, not to broadcast images of the performers but to capture the movement and cycles of the stage lights which then through video feedback create interesting loops and animated patterns. One song (“Push” I think?) also pointed the camera at the audience creating a mirror image of the band and their view of us which was really cool and created an amazing illusion of intimacy in a huge arena.

The main set opened with the song “Open” and ended with “End” — both from the album Wish, the followup to Disintegration. The story of Disintegration‘s commercial breakthrough is an inspiring one for anyone looking for an example where sticking to artistic vision instead of “commercial” advice yielded the most bounty. The early Cure stuff had a very dark and broody sound, very atmospheric and often somewhat slow for pop or post-punk. In other words, everything that radio programmers in the United States would consider anti-commercial, the opposite of “what people like to listen to.” After firing most of the band in the early 80s, Smith — with Lol Tolhurst in tow — carried on The Cure name by releasing, of all things, what were essentially alt-rock dance tracks with “Let’s Go To Bed” and “The Walk.” They charted. What followed were two very strong albums that codified The Cure’s ability to attack the pop music genres with idiosyncratic songs that simply don’t fit comfortably into any box but “music.” (Head on the Door and Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me) The selections were eclectic on these albums, veering from dark and raucous (“Torture,” “Shiver and Shake”) to playful (“Close to Me’) to depressing and uplifting at the same time (“Just Like Heaven”).

By all accounts in the media, the recording of Disintegration was a painful chore. Tolhurst spent the sessions drunk and contributed nothing to the recording and was dismissed/quit during the mixing. Smith himself sometimes refused to speak to anyone. He was depressed about turning thirty and had self-medicated with LSD for a year leading up to the recording. The album’s title seemed apt, as if everything in Smith’s world were fraying apart and the only thing to do was make a gorgeous tapestry of anti-commercial music out of it, trying to return the band to the dark sound of Pornography (1982, and incidentally probably my favorite album of theirs pre-1989). I’ve read various reports that execs at Elektra, the band’s U.S. record company, felt the record was commercial suicide. Who wants to listen to a six-minute dirge?

Lots of people, apparently. Disintegration went to number 3 in the UK and number 12 in the US, and “Lovesong” went to number two in the US singles charts. Up to that time that was the best they had ever done. The album went quickly gold, and soon platinum (and is now triple platinum worldwide).

The album that followed in 1992, Wish, vaulted from Disintegration‘s strong showing to debut at number one in the UK and number two in the States. The first single, “High,” charted very well, too, but it’s the “silly” love song “Friday, I’m In Love” that people remember best (though anyone who thought The Cure didn’t have silly sentimental love songs in them already weren’t paying much attention).

What struck me hearing the songs from Wish featured so prominently in the concert last night was that they seemed familiar to me but I didn’t have the visceral complete brain-body-spirit experience hearing them that I did with every other song and I wondered why. I kept wondering which album they were from and I was surprised to realize on checking the track listings that they were all from Wish. There is a Wish-shaped hole in my memory. I had to go to my CD shelf to see if I own it. I do. It’s there right next to Faith and Pornography. Perhaps y amnesia stems from the fact I was at the end of my rope depressed and waiting to hear if I was accepted into the Emerson MFA writing program when Wish came out. Or maybe it was just that nothing could quite live up to the benchmark that Disintegration had become.

I used to “mark” my albums, i.e. write capsule reviews of them and stick them to the cases. This is an old radio DJ practice, leaving your opinion about it so later you can easily recall what you thought and help you or your colleagues quickly decide whether to play a song from it next, when you have very little time to make that decision. This one is not marked and I think I know why. Because I couldn’t bring myself to write that after the masterpiece that was Disintegration, Wish was simply not that special. It felt to me like a follow-on. More of the same. Good, very good, but more of the same, and at that point in my life what I opted for instead was to listen to Disintegration a few hundred more times.

That meant hearing the songs from Wish in concert like this was a weird kind of deja vu. I recognized the songs and I liked them but I didn’t know them. Heard now, in the context of the entire Cure oeuvre on display last night, I realize that my reaction of Wish being lesser than Disintegration was more about me and the impact of that album on my life–and the lack of impact of Wish–than anything about the actual music. The music itself, yes, is “more of the same” because when you hear the breadth of what The Cure do strung together into a seamless performance on stage you realize it is all of a piece. It all fits together. As it should.

The main set spanned sixteen songs and did not end until nearly 10pm. I was thrilled to hear “The Walk,” which I consider a fairly obscure track but given that I played/sang/sequenced it on my 23rd birthday is still a personal fave. Every song was a “crowd pleaser” though, causing people to erupt with delight. The man next to me, a bald, goateed middle-aged guy, probably my age (49) and not apparently emo in any way, burst into tears when “A Night Like This” began and cried/danced happily through the entire song.

The “paradox” of The Cure that non-goths often can’t grasp is how a collection of songs that repeatedly mention love, Christmas, and cats can be moving rather than frivolous. Those of us who grew up goths can tell you though, the world looks different when you’re not afraid to feel or express negative emotions. The world *is* different when you make mortality and tragedy your bedfellows (and explore them through your art) instead of the things you gawk at, deny, push away, or hide at every possible turn.

Then there’s the fact that the music is so good. Maybe Robert Smith could write about anything and it would still be just as good. He’s been known, apparently, to go completely off the lyric sheet when performing in Japan or other non-English-speaking countries and just speak in tongues and invent new lyrics.

He stuck to English last night, though. When the main set was over, the crowd clamored for an encore and upon returning to the stage Smith actually addressed the crowd for the first time. The opening set had been played without any pause between songs other than the quick change of guitar here and there and no patter at all. The only one on the stage with a mic is Smith–no one else sings or speaks. Coming out for the first encore, he told us “This is a new song,” and launched into the playing of something called “It Can Never Be The Same”–the same words that are emblazoned in white letters across one of his black Schechter “Ultra-Cure” guitars. (The other guitar of the same model he used in the concert has numbers in the Fibonacci series: 1-1-2-3-5-etc. See photos of them here: https://www.facebook.com/easycure96/posts/10153812172679678)

During the performing of “It Can Never Be The Same” Smith became very emotional, first time I’ve seen that from him. Overall Smith’s emotions are on display for those close enough to see his face–and for the first time I realized the black eyeliner and slash of red lipstick are essentially functioning as a mime mask for him, accentuating each cringe, smile, and grimace. With no words addressing the crowd during the main set at all, all of Smith’s communication is through his face and body language and up close I could see him making faces at us, sometimes self-deprecating, sometimes concerned, sometimes moved, but most often he seemed delighted, and the crowd also reacted to most things in the show with delight. Not an emotion I would have picked for the top five to associate with The Cure. In Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series, Delight has been corrupted into Delirium, a twisted version of her former self, but on this night it was like The Cure restored her to her rightful state. The “Cure” for what breaks us in modern life? A cure for the darkness and pain we’ve been through of late, Bowie and Prince, and the shooting in Orlando, and every other thing that beats down the weirdos we feel we are inside? Now that Bowie and Prince are gone, Robert Smith is one of few icons left bearing the “it’s okay to be weird” torch.

Perhaps the temporary expression of pathos and pain in “It Can Never Be The Same” was part of the medicine. Smith didn’t break down enough to stop the song but whatever it’s about for him, it’s affecting him deeply. I couldn’t make out all the words but with a title like that and what I could hear of it, I couldn’t help but think about how nothing’s been quite the same in my interior world since Brian died. (Lover of mine killed in a motorcycle accident a few years ago.) One fan has posted a first stab at transcribing the lyrics and they do seem to fit: https://craigjparker.blogspot.com/2016/05/it-can-never-be-same-lyrics.html. I’ve seen speculations that the song could be about Robert’s mother passing or it could be about Bowie. It’s of course both because Cure songs rarely are “about” merely one thing, which is part of what makes them as deep as they are. No, nothing ever is the same, yet life goes on, we go on, and music ensures there is still joy in the world.

The first encore had another of my favorites, “Burn,” the opening track to the soundtrack album for the 1994 movie The Crow, which I probably don’t have to tell you was a(nother) breakthrough moment for goth subculture into the mainstream. Another connecting thread to that watershed year (for me and The Cure) of 1989, the original comic book of The Crow began appearing in February 1989: my boyfriend and I purchased it in our regular weekly comic store run. I reviewed it in our comic book zine (it was the era of zines) and sent a copy to James O’Barr who wrote back thanking us for the support.

Both “Burn” and the song that preceded it, “The Snakepit,” featured Smith playing a bamboo double flute which had been hanging on his mic stand for the entire show. I kept wondering what song it was going to appear in and was trying to remember if the flutey sounds in “The Snakepit” and “Burn” were actual whistles or just synthesizers. It was interesting to see Smith add these sonic flourishes the analog way and to draw the connection between those two songs so tightly.

I felt many of the songs could have been reordered and it wouldn’t have mattered. The Cure’s music is one large aural tapestry that, in hindsight, is whole cloth and not “eclectic” at all.

To open Encore #2, Smith again addressed the audience. “I was never one for nostalgia, I know that’s a surprise, but we played this song here in Boston on my 21st birthday so here it is tonight.” They launched (slid?) into “M” from Seventeen Seconds and the other two songs in the set were also from Seventeen Seconds: “Play for Today” and “A Forest.” I’ve always considered both of those songs to be underrated and was extremely happy to see them be featured thus. (Meanwhile for footage from that 21st birthday concert and Boston’s short-lived but influential venue, The Underground, check out this multi-camera footage from an MIT alum: https://www.vanyaland.com/2016/01/14/watch-rare-1980-video-of-the-cure-playing-a-forest-in-allston-on-robert-smiths-21st-birthday/.)

Encore #3 brought two more mega-hits onto the stage with “Lullaby” and “Friday I’m in Love” in a four-song set, one from Disintegration and the other three from Wish. “Lullaby” was completely mesmerizing as Smith’s face essentially contorts through both the role of victim and spider. They left the stage after “Friday I’m In Love” leaving us wondering if that was the note they were choosing to leave us on.

But the lights didn’t come up and the crowd didn’t let up chanting and waving their phone lights and the next thing you know they came back from a fourth and final encore. This time we went back in time again, every song from 1987 or earlier, starting with “The Perfect Girl” and then a succession of uptempo hits so essential once they were heard it was like “oh of course, they couldn’t leave this one out, could they?” “Let’s Go to Bed,” “Close to Me,” “Why Can’t I Be You,” and finishing with the oldest song they’d play all night: “Boys Don’t Cry.” Smith picked up his guitar before the first song, but then as the rest of the band kicked in he took it off almost sheepishly and then did the entire last set without one, singing only.

(Note how the lights and video boards are interacting.)

After the final notes rang out, Smith walked the edges of the stage taking his bows and seemed reluctant to leave. In “Let’s Go To Bed” he sang “If you think you’re tired now, just wait until…seven!” instead of the usual lyric, “three.” And at one point remarked, “I wish we could play for another three hours.” But I’d overheard security guards before the show saying that the floor had to be cleared by 11:30. It was 11:20 when the lights came up and roadies began dismantling the stage instantly.

When I next checked the time it was 11:30 pm as I exited the arena. My knees were swollen and my feet were tired but my soul was content in a way that it wasn’t after the show in 1989. And I have a strong feeling the same is true for Robert Smith.

Full Set List with albums and original release dates:

Main set:

1. Open (Wish, 1992)

2. Kyoto Song (The Head on the Door, 1985)

3. A Night Like This (The Head on the Door, 1985)

4. Push (The Head on the Door, 1985)

5. In Between Days (The Head on the Door, 1985)

6. Sinking (The Head on the Door, 1985)

7. Pictures of You (Disintegration, 1989)

8. Closedown (Disintegration, 1989)

9. Fascination Street (Disintegration, 1989)

10. Hot Hot Hot!!! (Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, 1987)

11. The Walk (stand-alone single, 1983)

12. The End of the World (The Cure, 2004)

13. Lovesong (Disintegration, 1989)

14. Just Like Heaven (Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, 1987)

15. From the Edge of the Deep Green Sea (Wish, 1992)

16. End (Wish, 1992)

Encore 1

1. It Can Never Be the Same (new song!! debuted on this tour)

2. The Snakepit (Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, 1987)

3. Burn (The Crow soundtrack, 1994)

Encore 2:

1. M (Seventeen Seconds, 1980)

2. Play for Today (Seventeen Seconds, 1980)

3. A Forest (Seventeen Seconds, 1980)

Encore 3:

1. Lullaby (Disintegration, 1989)

2. High (Wish, 1992)

3. Doing the Unstuck (Wish, 1992)

4. Friday I’m in Love (Wish, 1992)

Encore 4:

1. The Perfect Girl (Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, 1987)

2. Let’s Go to Bed (stand-alone single, 1982)

3. Close to Me (The Head on the Door, 1985)

4. Why Can’t I Be You? (Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, 1987)

5. Boys Don’t Cry (Three Imaginary Boys, 1979)

Boston METRO has some nice photos where you can see Reeves Gabrels, Simon Gallup, Roger O’Donnell, and Jason Cooper, too: https://www.metro.us/entertainment/the-cure-amplifies-agganis-arena-photos/

Oh, and I forgot to mention that although Reeves Gabrels (guitar) has let his hair go completely white a la Brian May of Queen, Simon Gallup (bass) appears to have NOT AGED since the 1980s. I knew it was him and yet I kept thinking they must have gone out and gotten a twenty-something guy who holds his bass the same way to replace him. Roger O’Donnell was on keyboards and Jason Cooper on drums to round out the ensemble.

I was at the Underground gig in 1980.

So was Bob Colby!