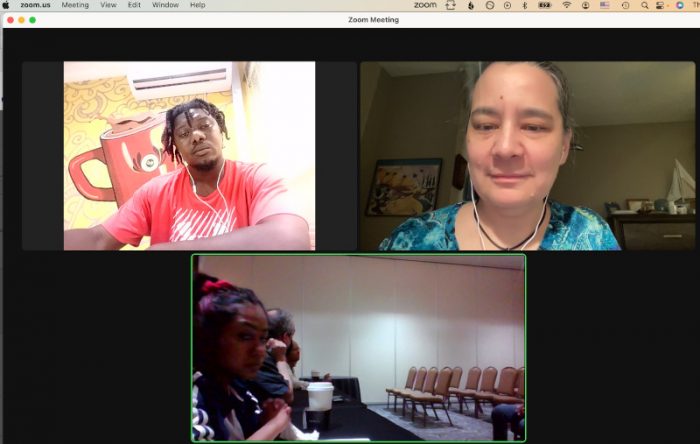

This morning was the ICFA panel on “Editing Beyond the Non-Western World,” which was intended to feature guest of honor Oghenechovwe Donal Ekpeki, as well as myself, Mary Anne Mohanraj, Neil Clarke, and moderator Mimi Mondal. As it has turned out, Oghenechovwe was detained when he traveled to the USA to attend the NAACP Image Awards and denied a visa for entry, meaning he could not attend ICFA, either. And I am missing the convention also, even though I’m currently only a 90-minute drive away, because I’m in the Tampa area where my father’s health is failing. (He was giving last rites in the hospital a few days ago when his doctors believed his expiration was imminent, so I cancelled my plans to go to Orlando, but now that he is home and having home hospice care, he seems to be holding up…! Thank you everyone for all your good wishes and prayers!)

Although the panel room had no WIFI, Mimi had the idea to try to bring us into the panel via Zoom using her own cellular data plan, and this effort was largely successful, but in many ways was a perfect metaphor for the difficulties of publishing writers from outside the USA or Great Britain. One common theme of the panel’s remarks was that there are systemic and logistical barriers to entry for writers from the non-Western world, including issues with currency conversion and difficulty of access to markets and source materials. And another theme was how often the only entities redressing the situation were individuals applying their own resources.

The panel opened with the panelists introducing themselves, and one common thread among us has been our tendency to go out and start things for ourselves. I founded Circlet Press to publish erotic sf/f when no one else would; Mary Anne Mohanraj founded Strange Horizons, but also Clean Sheets at a time when erotica and sexuality markets were disappearing, and also the Speculative Literature Foundation; Oghenechovwe had to take the lead in publishing the anthologies of African science fiction that he is well-known for; and of course Neil Clarke is the publisher of Clarkesworld.

What follows are some notes on some of the remarks made on the panel, based on my notes. I didn’t attempt to capture a true word for word quotation except here and there, and I don’t have notes on my own statements since of course I was talking at the time and not writing things down. But I thought it would be useful to blog this portion of it.

Neil’s direction of Clarkesworld has included the approach of including a translated work in (almost) every issue, “to normalize it.” He told the story that when he embarked on the project of publishing sf/f in translation, many people urged him to “do a special issue” or an anthology, but his argument was he wanted to normalize reading and enjoying the varied perspectives from non-English-speaking writers. “Too often they are treated as a special case.” He looked into the history of such anthologies and came across an International Science Fiction anthology edited by Frederick Pohl. Lester Del Rey wrote the introduction to that volume and in it he blamed the US science fiction market for ignoring the rest of the world. Neil tracked down the exact quote: “…[O]ur stories are sent to large numbers of fans and translators all over the world, while our own authors and fans seldom get even a hint of the work being done in our field by others. We’re in serious danger of becoming the most provincial science-fiction readers—and writers—on earth.”

Del Rey was prescient. That’s the situation we find ourselves in today.

Mary Anne Mohanraj spoke about working with writers from some other countries, including Pakistan and Sri Lanka, and finding both the language and the style of story many writers were telling felt dated, like they were stuck in the 1960s, and in fact when she went to bookstores in India and Pakistan, the works of sf she found on the shelf were “classics” of sf like Heinlein from the 1960s. “But they’d never heard of Samuel Delany, who I consider one of the all-time greats,” she lamented.

Ebooks and the online magazines have helped this problem of access somewhat, Clarke pointed out, but you can also track the influence of what gets translated out of English into other countries “like an invasive species.” Everyone on the panel lamented the phenomenon of English-language sf writers being lionized over local and indigenous writers.

Some paraphrases from my notes:

Mimi Mondal: I traveled all over the area of India where I am from taking photos of the sf section of bookstores, and the only writer of color on those shelves was Rebecca Kuang. I tried to handsell my own book some times and they are almost less interested in Indian writers than the white imports. They want “Seth Dickinson.” That sounds like a “science fiction writer” to them.

Neil Clarke: There’s a pedestal effect. The US market is still considered the “important one.”

Mary Ann Mohanraj: While editing a Pakistani writers anthology, I learned Urdu has a tradition of long, lyrical narratives, and you see it reflected in the style of the writing, even in English. But to a commercial fiction editor or reader it comes across as slow.

Mimi Mondal: The American market also has expectations on “foreign” writers. A women who writes bestsellers in India, but whose themes are very dark and very sexual, her literary agent could not sell these works in English. It isn’t that she isn’t a good writer or even a proven seller! It’s that the US doesn’t “expect” that type of material from a South Asian woman.

Oghenechovwe Donal Ekpeki: Regarding expectiations, so much of editing and reviewing is driven by expectations. Reviewers will say “this was good, and that was good, but I still don’t like it.” They can identify why a story is good or why the writing is good, but not why they don’t like it. Reviewers need to be familiar with a type of story because it will shape thei expectations. The stories that come in an “African” anthology get much more appreciated, get much more notice for awards, get much more praise from reviewers, than the stories in “bigger venues (i.e. Asimov’s) but that don’t have the “African” label on them. The label sets people’s expectations. It won’t be like Asimov’s which has only had a few African writers. The stories in my anthologies get more awards instead of disappearing. By having a space that is defined as our own, it helps to create that expectation. Publishing the translations in Clarkesworld helps to normalize them, but. These days I am now a popular name in short fiction. The magazines have built a reputation for me, so I don’t get lost, but others do.

Neil Clarke: We definitely need both approaches, a two-pronged approach to the problem.

Mimi Mondal: Certain subgenres have narrow expectations as well, like urban fantasy is supposedly saturated, where the readership just wants material from the same ten writers over and over.

Mary Anne Mohanraj: One thing I feel I should mention is the effect of theocracy. I went to Pakistan to work with 14 writers, mostly age 31-40, ten women and four men. And I didn’t really understand how much social pressure they are under in a theocracy. If they wanted to write about LGBTQ issues, for example. Some of the women were queer and they told me I was the only other queer writer they had met. It’s literally illegal to publish blasphemy. These students had never read Salman Rushdie because of the fatwa. One student had a story that had the concept of god as female and the whole class was like you can never publish that, or only under a pseudonym, or you’d be in danger. I’ve never had to deal with that level of threat in my own creative life.

Mimi Mondal: The thing is within various cultures there is a certain way to write about queerness that is coded. And everyone within that context understand what you are writing about. But then if you send it to an English editor, they are like “what? who’s gay in this?”

Cecilia Tan: Ditto what Mimi said. One experience I had editing erotic sf/f was that we often needed to encourage the writers to put the sex scene in that they had left out, because they assumed that it wouldn’t be allowed. And I’d have to explain that the reason Circlet Press exists is to publish those things that no one else will.

Audience member question: I was in a book club that read Remote Control (by Nnedi Okorafor) and they just hated it because it’s not told in a traditional European-style narrative. How do I convince them to branch out and try new things?

Neil Clarke: Well, you can’t just “convince them,” but the great thing about short fiction is that you can expose people to things in small doses. You aren’t going to like every story in a magazine, but if you read them all you will find some you like and some you don’t. It’s one way to expose people to some styles and ideas they might not stick with in a whole novel.

Cecilia Tan: One interesting parallel to this is the world of food and cuisine. When calamari was first introduced the menus in the US, it was considered a weird and exotic food, but there was overfishing and a surplus so the US government literally encouraged restaurants to buy it up and start serving it. And their suggestion was make it an appetizer, because that’s less threatening. People will try something new if they know they’re only getting a little taste of it and not the whole main dish. It worked so well that calamari is now the number one appetizer served in the USA today! [At the time I said octopus, but calamari is actually squid, of course…]

Mimi Mondal: Academic syllabi are also a place where people are open to trying new and different things. They expect to be exposed to things in a class. Mold some young minds!

Mary Anne Mohanraj: I like to share syllabi on the SLF site! The canon is rigid and annoying, but it can be changed and expanded, slowly.

And then our internet connection crapped out, so I didn’t get to hear what folks’ closing statements were, if any, but thank you very much Mimi for making sure we off-site folks were able to put in our two cents! I hope to be back at ICFA in person next year.

Update: Oghenechovwe Donal Ekpeki is fundraising to help settle the visa issues. See more details at the GoFundMe page: https://www.gofundme.com/f/oghenechovwe-ekpeki-visa-processing-legal-fees